layouts/_default/single.html:

Ep 8 - Forensic Science: Fighting Crime!

Download on Apple… Spotify… Amazon Music

About The Guest: Professor Dennis McNevin

Professor Dennis McNevin is a forensic scientist from the University of Technology, Sydney.

He has extensive experience in catching criminals and developing methods for extracting and preserving DNA.

He’s worked with the Australian Federal Police and has provided forensic training to police services in various countries.

Summary of Episode:

This episode covers the history of forensic science, the role of DNA in solving crimes, and the use of technology and equipment in investigations.

Professor McNevin also addresses questions about privacy concerns related to DNA testing and the possibility of getting away with murder.

The conversation is super light-hearted and humorous, providing both an entertaining and informative look into the world of forensic science.

The Origins of Forensic Science

Forensic science has a long history, dating back centuries.

It is the practice of solving crimes by analyzing evidence left behind.

As Professor McNevin explains, “All societies have laws, but of course, some people always like to break them. And so you want to find who broke the rules or the laws and how did they do it.”

The modern practice of forensic science as we know it began about a hundred years ago with Edmund Locard, who established one of the world’s first forensic laboratories in Lyon, France. Locard’s famous phrase, “Every contact leaves a trace,” became the foundation of forensic science.

The Intricacies of DNA Analysis

While DNA analysis is a powerful tool in forensic science, it is not without its limitations. Professor McNevin explains that the quality of DNA obtained from different sources can vary. For example, DNA extracted from hair tends to be of poor quality, while blood provides high-quality DNA.

Additionally, DNA analysis can only provide information about the presence of DNA at a crime scene, not how it got there. DNA can be transferred through various means, such as touching an object or breathing on it. This means that finding someone’s DNA at a crime scene does not necessarily mean they committed the crime.

The Privacy Debate

The use of DNA in forensic investigations raises important privacy concerns.

Professor McNevin highlights the division of public opinion on this matter. Some companies, like 23andMe and Ancestry.com, emphasize privacy and pledge not to share DNA data with law enforcement.

On the other hand, companies like Family Tree DNA market their services as a way to help solve crimes. This debate raises questions about the potential misuse of DNA data and the need for stronger privacy laws.

Solving Cold Cases

Advancements in forensic science have allowed investigators to solve cold cases, which are crimes that have remained unsolved for many years.

Professor McNevin explains that as new techniques and technologies are developed, evidence from cold cases can be reanalyzed to uncover new leads. This has led to the resolution of cases that were once considered unsolvable.

The Future of Forensic Science

As technology continues to advance, the field of forensic science will undoubtedly evolve. Professor McNevin mentions the possibility of using DNA to create facial reconstructions of individuals, although this technology is still in its early stages.

He also highlights the importance of staying ahead of criminals who may use forensic science knowledge to commit more sophisticated crimes.

The ongoing development of forensic techniques and the integration of new technologies will play a crucial role in the future of crime-solving.

Conclusion

Forensic science is a fascinating field that combines scientific analysis with criminal investigations. DNA analysis has revolutionized the way crimes are solved, providing valuable evidence and insights.

However, it is essential to recognize the limitations and ethical considerations surrounding the use of DNA in forensic investigations. Privacy concerns and the potential for misuse of DNA data must be carefully addressed.

As we continue to unlock the mysteries of forensic science, we gain a deeper understanding of how crimes are committed and solved. The future holds exciting possibilities for advancements in technology and techniques, ensuring that forensic science remains a powerful tool in the pursuit of justice.

TRANSCRIPT

00:02

Hello and welcome to Big Questions from Small Minds, the podcast where we ask professors questions that seem too massive, too complicated or even stupid. We also have lots of intelligent questions. No, not ours. They’re questions from actual small minds, children’s. Have you ever watched one of those crime shows and thought, is that how easy it is to solve? Well, Tom, today we’re talking forensic science with Professor Dennis McNeven from the University of Technology Sydney.

00:31

He’s all over catching bad guys. His work includes developing methods for extracting and preserving DNA. I’m guessing that’s like a super DNA vacuum and a nice big fridge to keep it in. He has established a genetic ancestry laboratory to provide intelligence services to forensic investigators. That’s probably a big book of genetic mugshots. And in the past, he’s worked with the Australian Federal Police and that’s where lots of his graduates go to work. I bet none of them get warned they’re gonna be touching gross stuff.

01:01

and internationally, he’s delivered forensic training to police services in Indonesia, Thailand, Iraq, and Pakistan. Awesome, because if you ever thought about committing a crime, this professor is gonna tell you why you’re an idiot. You’re never gonna get away with it. How does your brain work? What will the world be like in 100 years if we don’t fix climate change? Why do I have to sleep? Can robots have emotions? Big questions from small minds.

01:29

Dennis, thank you so much for coming on. It’s great to be here. Nice to meet you, Tom and Phil. Nice to meet you. So forensic science, what is it? How did it begin? Look, it’s really been going for centuries because it’s all about solving crimes. All societies have laws, but of course some people always like to break them. And so you want to find who broke the rules or the laws and how they do it. But the modern…

01:57

The practice of forensic science as we know it probably started about a hundred years ago with a guy called Edmond Locard. He lived in Lyon in France. Bonjour. And he set up one of the world’s first forensic laboratories in Lyon. He was the one that came up with the phrase that we always use in forensics called Every contact leaves a trace. Oh my god, that’s what I said.

02:25

Do you reckon that was because when he was eating his croissants, there would be crumbs everywhere? Well, that’s a nice analogy, actually. If he was to leave his breakfast table and go into another room, someone could perhaps tell by the croissant crumbs that he’d been eating a croissant. Evidence of his prior actions. Monsieur, monsieur, here’s your evidence. It was delicious. Every time you touch something or come into contact with it, you leave something there.

02:54

It might be a hair, it might be a finger mark, or it might be your DNA. What about smells? Smells? We do leave those behind. Can you tell from a smell? Can you grab a jar and bottle it? Well, it’s not a standard forensic practice. In fact, in my previous life as an engineer, my engineering job was to get rid of smells. Oh wow. And the way I used to do it was to pass it through

03:23

what was called a biofilter, which is like a cylinder of dirt. The smelly air would go into the soil and all the microorganism in the soil would chew it up. Right. And then it would come out clean on the other side. That’s like when you’re a kid, then you’re playing video games and you think no one’s going to smell it and you sink the fart into the couch. That’s right. But it’s there. You’ve left a trace. That’s why you need to have a couch full of dirt and you’ll be fine. But there were people developing the electronic noses.

03:52

to try and detect the compounds in these odorous gases. Disgusting. I hate this job. Things like hydrogen sulphide, which is a really smelly one, that’s the rotten eggs. Please kill me. And scatols, they’re basically organic compounds that make your farts smell really bad. Next time one of those happens, I’m just going to be like, I’m just being organic. That’s right. And you can train these electronic noses, which are basically devices which turn.

04:18

the contact with a smelly compound into an electrical signal. So you can power the world by farts. It’s a visual. You could. You could compose music. Wow. The smell sensor can have different levels of like notes. This is genius. We don’t need to start that idea. Barbed written tunes. Do forensic scientists just solve murders or do they solve other crimes too? Not just murders. So murders are.

04:46

what we call high profile crimes, but there’s other crimes that are commonly referred to as volume crime. So that’s things like break and enters and car theft. It’s a property theft.

05:00

They’re nevertheless crimes and they affect people’s lives. And I’m sure that there are people listening to this who’d hate it if they came home and they’d been robbed. So those crimes are, yes, still important. And yes, forensic scientists are involved in solving those crimes as well. You’ve basically got a superpower of solving crimes. So whenever there’s a mess at home or something, you’re at a local bridge. Do you do you can figure out who did that? Do you drive your partner crazy?

05:30

Yes, but not for those reasons. Look, to be honest, what you’re talking about there is probably the skills required of a criminalist. Now, I’m not a criminalist. I’m a forensic scientist. So the criminalist will be responsible for collecting stuff at the crime scene. And then they send that stuff to a forensic scientist and say, listen, can you get DNA from this or can you get a fingerprint from this? But it’s the criminalist who’s responsible for all of those kinds of insights that you’re talking about and for solving the crime. Do you ever give people evidence to go?

05:59

Oh, by the way, it’s like I ruined the end of the book for them. We’re not allowed to say that. Because it ruins the job for them. It takes the surprise away. I would be a bad forensic scientist if I went to court and said, yeah, he did it. What I should be saying is it’s very likely to see this evidence if what the prosecution says is true. That’s all I can say. I can’t say, oh, he did it.

06:25

What’s DNA? And is my twin brother’s DNA the same as mine? Very good question. DNA is a very long molecule. A molecule is just the particles that we’re made of. And this long molecule called DNA, which stands for deoxyribonucleic acid, is like a code. I liken it to IKEA instructions. Now, when you buy furniture from IKEA and your parents…

06:53

get divorced over trying to assemble a bookcase because they can’t read the code properly. Well, DNA is like that. It tells your body what color eyes to give you. Brown eyes. Green. Blue eyes. How long your legs should be. I wanna be tall. And how fast you might run. Like a cheetah. And it does all this by producing other kinds of compounds called proteins, which are the building blocks of what we’re made of.

07:20

So the DNA creates a Lego to build you. That’s right. It’s very much like Lego. So if you found blood in a crime scene, how easy is it to get the DNA from that blood and go, the person who left this blood behind has red hair compared to if you found someone with red hair. And you could go, the person with his red hair has this type of blood. Is it the same kind of work either way or is one much harder? The DNA in the hair tends to be pretty messed up. It’s dehydrated and you get a pretty poor quality DNA profile.

07:48

It’s hard to get good quality DNA from hair, but you get very good quality DNA from blood. You can then look for bits of DNA that are predictive of hair colour. And because DNA, as I said before, codes for everything in your body, including your hair colour, you can predict the hair colour of the DNA donor just by looking at their DNA. Is there any computer programs that can take the DNA and give you a kind of sketch of what the person looks like? Well, there is a company actually that purports to do that.

08:18

They provide pictures of people that they say have been developed from DNA and police do use them. Wow. I think some of those faces might look like more than just one person, but it’s not impossible that one day we might be able to produce a picture of someone’s face from their DNA. But I don’t think my DNA now would have predicted that I had a broken nose or a cracked cheekbone. That’s right. So the DNA only tells you so much. There’s other lifestyle factors which play as well.

08:47

But DNA does have a fairly strong influence on what we look like. And you only have to look as far as identical twins to see that. But identical twins have got exactly the same DNA. So those twins look a lot alike, not exactly alike because of these other environmental influences, but they look similar enough that it makes us think that, well, you know, DNA really does influence what we look like. Right. And if you’re wondering about how to tell the difference between identical twins, it’s the hat. I was going to say you should find out because

09:16

They sound like the perfect criminal pair. Oh no, it was him. It was him. It was him. Damn it, we can’t tell. It actually has been used as a defence. An accused person has good reason to say, oh, it wasn’t me. It was my missing brother. And the reason for that is because you share more DNA with your relatives. And so the pool of possible candidates that could match your DNA is much less. But of course the brother has to be missing because if they’re not missing, well, they can just say, oh, we’ll just go and get some DNA from your brother and we’ll just exclude them.

09:45

So if you’re thinking about committing a crime, hide your brother. Hide your brother. That’s right. Or just don’t commit a crime. But there have been a couple of like wrongful convictions with DNA. What generally causes these errors? One of the biggest problems is just because you find someone’s DNA at a crime scene doesn’t necessarily mean that they committed the crime. Can DNA fly? Well, it can’t fly as such, but it can be transferred.

10:14

Let’s say after this little podcast, we’re all in the same room here, shaking your hands, maybe rubbed shoulders with you. Grabbed a jar and bottle of fart. Yeah, exactly. Then I go somewhere else and I’ve got your DNA on me. And I might then grip a baseball bat or a hammer that’s used to break and enter. And I’ve suddenly transferred your DNA onto that. And then when the police come,

10:39

They might find your DNA on that hammer at the crime scene. Put your hands on your head. And you say, I wasn’t there. You were under arrest. But your DNA was. Wow. But your DNA would be there too. Yes, but some people shed DNA more than others. Like a cat. That’s right. It could be that you are more cat-like. And shed DNA. I mean, the other possibility, of course, you may have been there the night before and have left your DNA because you were invited over for a drink.

11:08

before the crime was committed, which doesn’t mean that you’re guilty of the crime. If I go into a room and shed my DNA, say I drop some skin cells on my hair, how long does that sit there? It could be weeks, it could be months. There are cases that have been solved where blood stains have been stored in an envelope at the back of a police station and 50 years later you still get a DNA profile from it. You can get DNA from woolly mammoths that have been preserved in the permafrost in Siberia.

11:34

feel like our neighbors about to get broken into by a woolly mammoth. What cool equipment do you use to solve crimes? Actually, there’s lots of equipment that can be used and some of it’s not that complicated. So one of the most useful things at a crime scene is a light, a colored light. Like a blue, a green, a red. All of the above. That’s why disco crime scenes are always solved very quickly. That’s why it’s always in the dark. Yeah. If your hair beats coming from a crime scene, it’s not a party.

12:03

It’s just a forensic scientist. But if you shine light at various angles, at surfaces, you can find all sorts of stuff. So different body fluids like saliva and blood, they will fluoresce, which means they give off light when you shine light at it. Your spit or blood will glow a little bit. So blood absorbs light, but saliva fluoresces. Like in the sea that you see it sometimes shining. Yeah, that’s right. Like colored jellyfish. And so that sort of helps you know what’s been left at the crime scene.

12:34

So often it’s very simple things that are effective in the first instance. But DNA is a different story, obviously. The way DNA is collected is usually with a swab, you know, like a cotton bud. You just dip the cotton bud in water or methyl. You swab where you think the DNA might be found on a bloodstain. Or maybe a door handle. Yep. Or a windowsill for break and enter. Or a spear handle. Yeah, for the mammoth. And take that back to the lab and you’ve got to extract the DNA out of that swab.

13:02

because it’s remember DNA is in cells and so you’ve got to break those cells open and release the DNA but then you’ve got to protect it once it’s released. Naked DNA is really easy to damage. For all those kids listening, yes he did say naked. Put your pants on DNA. I did. And then once you extract it you then got to amplify it up. It’s a bit like a photocopier. If you swab a fingerprint there’s not much DNA there so you’ve got to copy it up. It’s much like a photocopier. I’m going yeah yeah yeah a couple of times but now I’m going that doesn’t make any sense.

13:31

How do you do that? There’s a technique developed by a surfer in California in the 80s. A surfer? He loved surfing and that’s how he used to get his inspiration. Whoa, cow-bunga dude. He’s doing his floaters, he’s doing his cutback. That’s right. And he came up with the ingenious idea of replicating how DNA is copied in our cells. When our cells divide, DNA is copied. He said, well, let’s just do that process in a test tube. And so we copy DNA.

14:00

You double it each time. First you make two copies, and then it’s four, then it’s eight, then it’s 16. So very quickly you get to millions and millions of copies. Do you ever get mutations? You do. You get poor copies. And I’ll go back to the photocopy analogy. If you’re photocopying from an original, and then you photocopy that, and then you make a copy of the copy, then you make a copy of that copy, eventually the text gets a bit blurry. I remember doing that in high school, photocopying my face. I remember people photocopying their…

14:28

their bums. So you put a little bit of DNA into a test tube and you magically somehow make a million more of those DNAs. If you just left that test tube in a fridge for a while, would it turn into like a foot? No, because you’re only copying a bit of it and probably not the bit that makes the foot. Okay, but maybe like an eyeball. Maybe. I’m going to try that. Just get one fridge and then don’t open it again for a year. Well, there’s probably stuff I’ve left in there.

14:52

that would have been in there for just as long. Bags never go over to either of your places for drinks. Ha ha ha. Can you tell that I’m related to my grandma from our DNAs? And can DNA tell if I’m related to Genghis Khan? Yes and yes. You and your grandmother share a quarter of DNA. So you can compare the DNA from your DNA and your grandmother and it is possible to make…

15:21

an inference or to estimate whether or not you are related or not as grandmother, grandchild. And in fact, this has opened up a whole new world of criminal investigations just in the last three years. What could be criminal about bringing related to your grandmother? Well, there’s some pretty shady grandmothers out there. My Nana did smoke a bit of pot. No, it’s actually an interesting question because just three years ago, there was a famous case called the Golden State Killer.

15:50

and he terrorized a whole lot of people in the 80s in California and was never caught. The Golden State Killer continues to elude authorities. But they knew it was the same person because they’d got the DNA profile from all these crimes, but they couldn’t work out who it was. And one detective had an ingenious idea and he took that DNA and he uploaded it to one of those companies that do your ancestry. And they were able to locate their relative. I think it was a second cousin. Wow.

16:18

Did they just contact the second cousin and go, who’s your cousin? Yeah, but the thing is, each of us has probably got, you know, dozens and dozens of second cousins. So it’s pretty hard to narrow it down. But it’s still a lot less than a million people. That’s right. And they were able to use that information eventually to find this guy. And it turns out that he used to be a police officer. Can you believe it? That’s unbelievable. I can believe that. That’s unbelievable for you, but unbelievable for me. I’ve watched a lot of True Crime. Anyway, his name was Joseph James.

16:47

DeAngelo. He was 78 years old when he got caught, but he’d committed all these crimes and is now in jail for the rest of his life. That brings up a really interesting point. People need to start thinking about their DNA as almost like a privacy issue. Like if you’ve got your DNA forever uploaded to a government server and one day my great grandchild decides to rob a car and they can just be like, oh, we can put all these things together and bang. You’re absolutely right. And there is a lot of debate about this, about whether we should do it.

17:16

Can you claim privacy over something you left behind? Like your skin flakes and all that sort of thing. Oh, it’s not really intellectual property, is it? Like you left a fart behind. Yeah. But you have a intrinsic right to privacy. You do have an intrinsic right to privacy, but if you leave your information lying around, it’s kind of public domain. Well, legally it doesn’t make a difference. Like if you left a USB, sorry. Oh yeah, let’s ask the professor. Look, you both raise very valid points. And in fact,

17:45

There is a division of public opinion split roughly in each of your camps. 50-50. And in fact, in the US, there are companies that market to the public based on those two opinions. Your privacy is important to us. Together, we’ll help the police make a safer society. There are some companies like 23andMeandAncestry.com who say, we’re not letting police anywhere near your DNA. Today, protesters for stronger privacy laws took to the streets.

18:13

Hey, give your DNA to us. It’s safe with us. We’re not going to let the police anywhere near it. Until we get a better offer. But then there are other companies like Family Tree DNA who market to your side of the argument. Reports of police solving murder cases with ancestry DNA are increasing. Where they say, give us your DNA and help us solve crimes. You can help solve crimes with your DNA. A whole section of the population who say, oh, yeah, fantastic. I’m going to go for you because of that reason. Yeah, interesting.

18:42

That’s I’d like to put it that’s not actually my argument. My argument is like it’s your phone fault. You left skin flakes behind. We have to remember if you leave your DNA behind Tom and it’s picked up and it’s sold to an insurance company and let’s say they find out that you’ve got a predisposition for some disease and the insurance company says Tom we’re going to hike your premium because you’re more likely to die because we’ve read it in your DNA. Can I just say it’s my brother?

19:09

Well, that’s okay. Yeah, don’t worry about it. I see your point though. And it is a terrible, terrible thing. Everyone, your skin flakes should be free to roam free. I’ve been convinced that they are allowed to fly in the wind. And if anyone steals my fart, I’m coming for you. I mean, in two ways. Yeah. Could you find out who did a crime from a long time ago? Yes, you could. Every contact leaves a trace that I talked about before. That trace can persist.

19:39

cold cases, which that just means a case that hasn’t been solved for many, many years. And they often are solved as new techniques are developed to analyze evidence that weren’t available at the time the crime was committed. So who did shoot JFK? Yeah, I’m working on that one. I’ll let you know. What about Harold Holt? Do you know where he went? Swimming, apparently. Okay, I won’t keep hitting you with questions like that. Who knows? We may find…

20:07

Harold Holt’s skeleton washed up on a beach one day and we may be able to get the DNA from that skeleton. Or in the belly of a shark. Who knows. Well I thought they did find King Henry V in a car park in England. What, just wandering around? No, no, like they dug him up. Richard III, because I remember because he had a scoliosis or hunchback. He was a hunchback. Did they dig it up on a hunch? But he was indeed found in a car park. Apparently he was slain in battle.

20:36

And the record of the injuries that he received were consistent with damage to his skull. As you can see from this x-ray, his head was chopped like a cabbage. But also the DNA that was retrieved from the skeleton in the car park was traced through a particular type of DNA called mitochondrial DNA. And mitochondrial DNA only goes down the maternal line. What we mean by that is it’s from your mother. You don’t get it from your father. But it…

21:05

persists in a very unaltered form for many, many generations. And they were able to find someone who knew that they were a descendant of Richard the third, and they were able to match the mitochondrial DNA from the skeleton and this descendant. And that was pretty good evidence that this was Richard the third. Imagine a knock on the door. It’s like, hello, we’ve discovered a skeleton in a car park and we want your blood to see if it’s important. Oh, that’d be freaky. Like I didn’t do it. Yes, that wasn’t me.

21:35

Now it’s time for your favorite game show. Solving crimes with forensics. OK, I’m going to play a game with you, Professor. So I’m going to say a type of crime and you say the forensic way that mostly solves it. So the first one is murder. What’s the most common way that gets solved with forensics? Probably. Finding the perpetrator standing over the body.

22:05

in a rage. Okay, what about a bank robbery or heist while the bank is closed at night? Hmm. Wow. I would say tool marks used to crack the safe and to enter the window. Okay, great. What about a bomb? A bomb going off? So a bomb, you’re looking for explosive residues. Different types of explosives have different signatures, different chemicals that are used to make them up.

22:34

you look for those residues and you might be able to then find them on a suspect. And if that matches what was in the bomb, then that’s pretty good evidence. Last question. What about one of your students cheating? Well, look, it’s interesting you say that because we’re not allowed to give exams anymore. Since COVID, because in COVID everyone was at home, so you couldn’t have exams. And so a lot of universities have said, hey, we could do it during COVID. So let’s not have it now.

23:02

But there’s been a big increase in people cheating as a result because, you know, people do take home exams and the temptation is just too great. I think you can’t detect it. That’s beating the forensic professor. That’s right. The perfect crime.

23:20

Do crimes always have evidence? Is it really possible to get away with murder? Yeah, look, remember that DNA doesn’t tell you everything. So it just tells you that your DNA was there, doesn’t tell you how it got to be there. People do get away with crimes. It’s certainly possible. And not only that, but because everyone watches CSI these days, you know, the crime shows on TV. Do you love that joke?

23:44

No one likes to watch TV about their work. What part of CSI makes you the angriest? The fact that they’re all so glamorous and I’m not. You should see Professor Dennis. He came in here in a tuxedo. He looks amazing. He literally walked in low at his same last season and said, looks like someone’s about to commit entertainment murder. But actually, some of the instruments in those shows are real. Like the computers where they take the computers and the DNA and they put it in and, oh, it was that guy. The machines are real.

24:13

but you don’t just stick something in a machine that comes out five minutes later. It usually takes a few days to get an answer. That’s like when you’re listening to this program, it took a little bit longer to make, and it sounds like it may happen straight away. That’s the magic of editing. Take away our secrets. But the reason I mentioned those shows is because criminals watch them as well. And so they learn tricks about how to get away with crime. I guess it sounds obvious, but no one’s really thought about it until recently, is maybe you should wear gloves and a lab coat when you’re committing a crime,

24:42

leave your DNA behind. Maybe wear a face mask so you don’t breathe on stuff. Now, kids at home, I’m not trying to give you ideas about how to commit crime, but this is what criminals do. They’ve learned how to be better at committing crimes and to leave less evidence behind. And so you mentioned breathing out. Is there DNA in your breath? Well, every time you speak, your little droplets of fluid, your oral fluid comes out saliva and they all contain DNA because they’ve been swilling around in your mouth and your cheeks

25:10

in particular, shed cells into your saliva. And so yeah, your saliva is full of DNA. And when you speak, you just can’t help but spray people. So basically every time you have a meeting or go to school or whatever, you’re basically showering in other people’s spit. Sorry, that sounds super great. I’m going to have a shower. I mean, these microphones are going to be covered in our DNA. That microphone in particular has all the professors on it. I think we should just go and rob a bank and use that microphone to open the door. And the cop will be like,

25:40

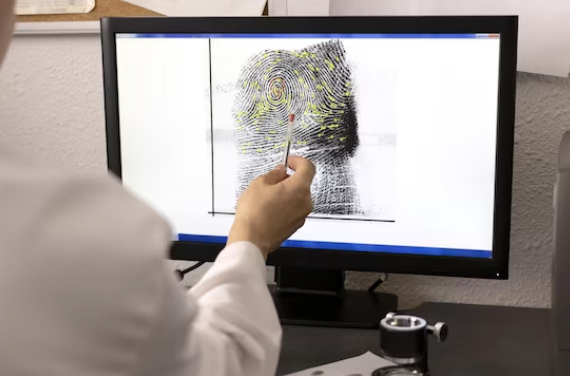

There’s 14 professors who’s brought this back. Mastermind criminal! Quick, look for the person who’s having the longest shower. So if I leave a fingerprint behind, is there DNA in that? Yep, you left two things behind. You left your fingerprint and your DNA, and that’s a very common practice in forensic investigations. But the big question is, what do we do first? Do we get the DNA first, or do we get the fingerprint first? Because…

26:03

By getting the DNA you might damage the fingerprint and by lifting the fingerprint you might damage the DNA. It’s almost like you can know how fast a photon’s going or you can know where it is but you can’t know both. Yeah. Or it’s almost like the classic, is the chicken not an egg? Or the other classic, eat your cake and have it too. And those are forensic questions that have never been solved. Well that’s why we’re here, we ask the big questions and we have small answers. Professor, thank you so much for coming on, it’s been extremely interesting. In fact, I’m going to go out and never commit a crime again.

26:33

That’s what you think. You shook my hand today. You’re committing all the crimes. And I’m going to go and break into your neighbours right now. If you want to find any of the information that we’ve talked about today, you can go to SmallMinds.au Keep curious people and keep asking the big questions. Big questions from Small Minds.