layouts/_default/single.html:

Ep 9 - Human Evolution: Bring It On!

Download on Apple… Spotify… Amazon Music

About The Guest: Professor Tanya M Smith

Professor Tanya M Smith is an expert in human evolution and the study of tooth growth and structure.

She’s held positions at Harvard University, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Currently, she’s a professor of Human Evolution at Griffith University.

She’s also the author of “The Tales Teeth Tell,” which explores the fascinating insights teeth can provide into human history and evolution.

Here’s a link to her brilliant book!

Find out more about Tanya on her web page or on wikipedia

Summary of Episode:

What are the origins of life? How are humans and other primates related? What caused the disappearance of Neanderthals?

And what they can the fascinating world of teeth tell us about our evolutionary history? In this episode we explore all these answer and the ways in which teeth provide a unique record of our past.

The episdoe is packed full with humor and curiosity, making complex scientific concepts accessible to all. Tanya’s book, “The Tales Teeth Tell,” is recommended for further exploration.

Exploring the Origins of Human Evolution

Human evolutionary biology traces its roots back to the groundbreaking work of Charles Darwin and his contemporaries in the 1860s. At that time, the idea that humans had an evolutionary history was highly controversial due to religious beliefs. However, as scientists began studying the evolution of other organisms, Darwin questioned the possibility of human evolution.

Professor Smith explains, “Evolution, if we think about it as change over time, can be observed in animals that don’t have long lifespans.

For example, birds. Darwin studied the finches, which were very famous. He was interested in the tradition of breeding animals, how animals could be influenced through their generations by the choice of their parents.”

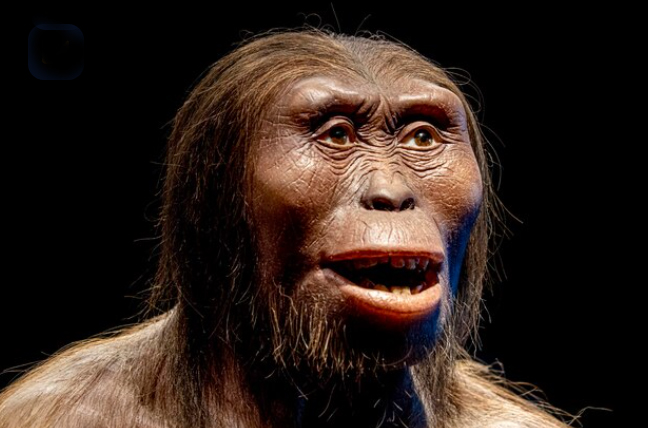

Are Humans Monkeys?

While humans are not monkeys, we are classified as apes. Professor Smith clarifies, “We are closely related to apes. We are more distantly related to monkeys, and we’re even more distantly related to things like lemurs.

So we are all primates.” This classification is based on our evolutionary history and genetic similarities.

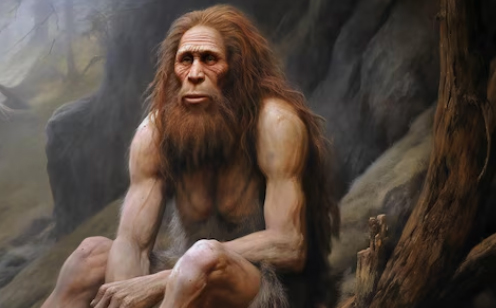

Neanderthals: Cousins or Distant Relatives?

Neanderthals, our ancient relatives, are much closer to us than monkeys or apes.

Professor Smith explains, “The evolutionary ancestor we would share with Neanderthals goes back less than a million years, whereas the evolutionary ancestor we’d share with the chimpanzee goes back somewhere like 7 million.” The exact reason for the demise of the Neanderthals is still debated among scientists.

It could be a combination of human aggression, climate change, or even the small size of their populations. Professor Smith adds, “If you can’t find a mate, that’s the end of your lineage.”

Evidence for Evolution

The evidence for evolution is based on deductive reasoning and the gathering of empirical evidence.

Professor Smith explains, “Evolution can be observed in animals that don’t have long lifespans. For example, birds. Darwin studied the finches, which were very famous. He was interested in the tradition of breeding animals, how animals could be influenced through their generations by the choice of their parents.”

By studying the changes in organisms over time, scientists can infer the existence of evolution.

Huamn Evolution

Human evolution is not a linear process but rather a complex web of interconnected species.

Professor Smith explains, “Humans are primates. We’re also mammals, so we share an evolutionary connection to all kinds of things that we think of as pets as well as large-bodied animals on the planet.”

The evolution of humans can be traced back over 200 million years, with various adaptations and changes occurring throughout our history.

The Mystery of Wisdom Teeth

Wisdom teeth, the third molars that typically erupt between the ages of 18 and 20, have long puzzled scientists.

Professor Smith sheds light on their purpose, stating, “The wisdom tooth is the last tooth to erupt in our mouth. So on average, we get that third molar about 18 to 20 years of age, if it ever comes.

And so that’s a marker of wisdom because everybody knows that 18 to 20-year-olds are the smartest people on the planet.” While the exact function of wisdom teeth remains uncertain, their late eruption is a unique characteristic of human dental development.

The Evolutionary Advantage of Two Sets of Teeth

Unlike sharks, which have infinite sets of teeth, humans have only two sets of teeth.

Professor Smith explains, “Humans are mammals, and some of the earliest mammals that we see in the fossil records had replacement teeth, just one set of replacement teeth. So that’s kind of a primitive condition that we share with all the other mammals.”

The specialization of human teeth allows for efficient food processing, making them more adaptable to a wide range of diets.

The Cultural Significance of Teeth

Teeth not only serve as a window into our evolutionary past but also hold cultural significance.

Professor Smith shares, “What’s really interesting is that it’s kind of a rite of passage to lose our teeth. And that’s true whether you grow up in Africa or you grow up in Europe or you grow up in Australia.

It’s something that we want to mark culturally.” The tradition of the tooth fairy, found in various cultures, symbolizes the transition from childhood to adulthood.

Teeth as Time Machines

Teeth are not only records of our past but also serve as time machines.

Professor Smith explains, “When you’re growing your teeth, you actually record every single day of your childhood, like the lines of a tree.”

By examining the microscopic timelines within teeth, scientists can gain insights into growth rates, developmental stresses, and even dietary patterns.

This information provides a unique perspective on our ancestors' lives.

The Impact of Culture on Human Evolution

While humans continue to evolve, our evolution is influenced by cultural factors rather than natural selection.

Professor Smith explains, “Our culture has kind of created its own selective pressure. So in the past, we think about being on the savannah, not wanting to get picked off by the lion. And so whoever could be smart enough to outrun or hide from or spot the lion was the one that made it.”

Today, our culture shapes our bodies and biology, leading to changes that differ from traditional evolutionary processes.

The Future of Human Evolution

As our culture continues to evolve, so too will our bodies and biology. Professor Smith notes, “It’s not the case that we’re not evolving anymore, but we’re not evolving in the way that we might have thought of.

All the other organisms on the planet are evolving.” The future of human evolution will be shaped by our changing environment, technological advancements, and cultural shifts. In conclusion, Professor Tanya Smith’s research on teeth provides valuable insights into the mysteries of human evolution.

By examining the chemical signatures, growth patterns, and cultural significance of teeth, we can uncover the secrets of our past and gain a deeper understanding of our shared history.

As we continue to evolve, it is essential to embrace our cultural influences and recognize the impact they have on our biology.

The tales teeth tell are not just stories of the past but also guideposts for the future of human evolution.

TRANSCRIPT

00:03

Welcome to Big Questions from Small Minds, the podcast where we ask professors questions that seem too massive, complicated or even stupid. We also have tons of intelligent questions. No, not ours. They’re questions from actual small minds, kids. We are taking a trip back to where everything began.

00:22

The primordial sludge. Ah yes, we’re talking to Professor Tanya Smith of Human Evolution from Griffith University. Previously, she was a professor at Harvard University and held fellowships at the Ragcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. You might say her career has been evolving. Tanya’s area of expertise is the study of tooth growth and structure,

00:52

about teeth and how through teeth she can uncover faithful records of humanity’s daily growth, diets and developmental stresses for millions of years all detailed in her book The Tales Teeth Tell. Believe it or not this podcast is going to be the pinnacle of human evolution. Honestly it’s taken us a long time to get this good. Such a long long time.

01:16

How does your brain work? What will the world be like in 100 years if we don’t fix climate change? Why do I have to sleep? Can robots have emotions? Big questions from Small Minds. Teddy, welcome to the show. Welcome to Small Minds. Thanks, Tom. Thanks, Phil. It’s really a pleasure to be with you. I’m excited to have a good conversation. Well, that’s what we want. Good conversations and silly questions. That’s our bag. Have you always, as a kid, wanted to be interested in…

01:43

where we came from? You know, as a kid I really loved to be in nature. That was my first draw to science. I just love the beauty and simplicity of being out in the bush, exploring the creeks, looking at things that were moving under the water and wondering about life and biology and how we came to be the way we are. So I was really interested in bones and…

02:02

you know, frogs and just basic things that I might stumble across as I was walking through the forest. So would you bring those things home to your parents and go, look, I found a bone. I would. I would try to raise up little tadpoles that I’d catch in the creek. So for people like me, what is evolutionary biology? Human evolutionary biology is something that started with Charles Darwin and his contemporaries. In the 1860s, you know, people were exploring ideas about evolution. They were studying how life changed through time.

02:29

And people started to speculate that humans too had an evolutionary history. And that was really controversial at that time because people held strong views informed by religion that people were created by God. And that was exactly how it was. So as scientists started studying the evolution of other organisms, Charles Darwin started to question the possibility that humans themselves had a deep time history. Did he ever discover that question that we all want to know? Was it the chicken or the egg?

02:58

I think he would say it was both. It seems like a cheap way out. Is my great, great, great, great, great times a million grandfather a little bacteria? Well, life began as some sort of single-celled organism. So we weren’t bacteria per se, but we think of bacteria as similar to this single-celled organism. I have no exact.

03:24

answer for you because no scientist has a precise answer. But we know that it was very simple. We know that chemistry and energy and structure somehow took on an animated form and it was very simple. It was again a single celled organism. And do you think there was a moment where there was just there was nothing and then all of a sudden there was something spinning around really quickly or did it arrive from space on a meteorite? That’s way over my pay grade. Are people monkeys?

03:53

We are not monkeys, but we actually are apes. So humans are primates. And that’s something that confuses people, particularly in this part of the world, because you don’t see too many non-human primates around you very often. But we are closely related to apes. We are more distantly related to monkeys. And we’re even more distantly related to things like lemurs. So we are all primates. I’ve heard that we also share the DNA with a cabbage. That’s so true. Yeah, we have a…

04:22

All living organisms share DNA. That’s the substance that underwrites life. But the amount of DNA we share with the potato and the banana is very different than the amount we share with other mammals, for example. Cats and dogs were more closely related to than vegetables, but we all have some of that same recipe inside us. That’s good, because I’d be very weird going to the shops and buying a bunch of bananas if I knew that they were my second cousins. Depends on how you feel about them. We’re dining on cousins tonight.

04:48

It’s now a cannibalistic podcast. If humans come from apes, what about Neanderthals? Are they a different branch of the same tree or are they from monkeys and we’re from apes? Neanderthals are much closer in terms of cousins than apes and monkeys would be to us. So the evolutionary ancestor we would share with Neanderthals goes back less than a million years, whereas the evolutionary ancestor we’d share with the chimpanzee goes back somewhere like seven million. But how did they die? What happened? That’s also highly debated.

05:16

That’s what we love here. One idea is that we had a hand in the demise of the Neanderthal. When she says we, she means you Phil. That’s right. She was looking at me at the time. We don’t actually know. We can suspect that it may have been human aggression, but also potentially climate. We also think that they lived in very small groups. So if you can’t find a mate, that’s the end of your lineage. Those poor, lonely, lonely Neanderthals. Sounds like they died of loneliness. They should have just made an app.

05:46

Tinder for Neanderthals. How do scientists know evolution is real? You know, we have a method of how we understand the world. We use deductive reasoning based on gathering evidence. Evolution, again, if we think about it as change over time, can be observed in animals that don’t have long lifespans. For example, birds. Darwin studied the finches, which were very famous. He was interested in the tradition of breeding animals, how animals could be

06:16

kind of influenced through their generations by the choice of their parent. It is not the strongest of the species that survives, not the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change. Bird breeding was something that influenced him because he could see how when different types of birds produced offspring, those offspring took on the characteristics of their parents. Ooh, she’s got her dad’s eyes.

06:41

Is it possible that we humans are evolving now and we’re going to get bigger eyes that we’re watching these screens all the time and our posture is going to change? Yeah, I don’t have good news for you, Tom. What is it? What’s the bad news? Our culture has kind of created its own selective pressure. So in the past, we think about, you know, being on the savanna and not wanting to get picked off by the lion. And so, you know, whoever could be smart enough to outrun or hide from or spot the lion was the one that made it to have a family and leave their offspring. Today it’s…

07:08

totally different. Our culture is what sort of affects our bodies and our biology and even our hormones. So the selection is, I would call it, almost artificial. It’s like we’re domesticated. We’re going to become fat cats. To be fair, our bodies have changed, for example, since we started farming. Our biology has shifted every time our culture shifts. So it’s not the case that we’re not evolving anymore, but we’re not evolving in the way that we might have thought of all the other organisms on the planet are evolving.

07:36

Some animals have teeth that turn into horns. Why don’t people have something cool like that?

07:44

Yeah, that’s a great question. You know, evolution tends to select for things that are advantageous for an environment. So when you think about an elephant with that beautiful tusk, that has a special function. It allows those elephants to dig or strip the bark from trees or maybe fight with one another. And that gave them an advantage. So those characteristics, or we call them adaptations, help them survive and reproduce and leave more offspring. Humans didn’t have that same pressure on us to have to develop a tool to be able to

08:13

dig in the ground, was in our face. We have our hands, we have our thumbs, we have our brains that allow us to manipulate our environment. So we didn’t need a structure. We had other ways of getting those needs met. We can make a shovel out of elephants task rather than grow one big giant tooth. Exactly. It’s a little bit of a let down, isn’t it? Yeah. Well, we can reduce your brain size and put some tusks on you and see how you go. I mean, I’m kind of down for it. I know a lot of people out there would be out for that. Yeah. There’s a cave man.

08:42

have a tooth fairy. We find a lot of baby teeth, in fact, in the fossil record. So somebody was pocketing them and maybe making a few dollars. Actually, the idea of a tooth fairy is something that’s really cross-cultural, and it’s not always a sprightly grandmother. In some cultures, it’s actually another animal that would be the collector of teeth. An animal? Like what animal? You could have a tooth rabbit? You could have a tooth mouse? Yeah. What about a tooth elephant? Haven’t heard of the tooth elephant.

09:11

It’s kind of very hard to sneak into someone’s room late at night. A toothed giraffe though with a long neck coming down. That’s why I have the long necks. What’s really interesting is that it’s kind of a rite of passage to lose our teeth. And that’s true whether you grow up in Africa or you grow up in Europe or you grow up in Australia. It’s something that we want to mark culturally. We want to acknowledge, you know, our children are going up, they’re developing, they’re maturing, they’re changing in their relationship to us. And so we mark that with this ritual, which is really lovely. And so you when you’re working with old teeth, when you dig one out of the ground,

09:41

Do you tell the person that takes it, they’re the tooth fairy because they’re taking it? Yeah, that’s right. All those careful excavators are the tooth fairies. No, it’s really a privilege to have the chance to study human remains. We consider that when you’re lucky enough to find something that’s been buried for thousands or millions of years, you know, you do treat that with respect. So there is no pranks that you guys do? I’ve never buried anybody’s teeth on purpose so somebody else could find them. I have to confess. What about someone’s grandma’s dentures? And like, oh, what’s that doing here?

10:10

I’ll see what I can do. Tooth is so small. What are the chances of me going for a walk in the bush and coming across one tooth? Yeah, I mean, there’s special places that preserve fossils and archaeological remains better than others. So you might study the landscape and see where particular surfaces were that were once ancient lakes, for example, because those tend to be good places for fossilization. And so are you really just getting the teeth of people who weren’t very good swimmers? The ones with the croc mark.

10:39

Why do humans only get two sets of teeth, but sharks get infinite teeth? Humans are primates, we’re also mammals. So we share an evolutionary connection to all kinds of things that we think of as pets, as well as large bodied animals on the planet. As well as cabbage. As well as cabbage, which is not a mammal. If you’re wondering.

11:02

We’ve got a professor to explain that. Official. Mammals evolved over 200 million years ago. And some of the earliest mammals that we see in the fossil record had replacement teeth, just one set of replacement teeth. So that’s a kind of a primitive condition that we share with all the other mammals, unlike fish, unlike reptiles, unlike amphibians. So this is part of this suite of adaptations that makes mammals so successful. So what you’re saying is that human evolution isn’t

11:31

very fishy. That’s right. Although we may have enjoyed fish in the past. So why is only having two sets of teeth an advantage over having teeth that you could break off any day and they would just grow back? Well our teeth are not just like shark teeth. They’re very specialized. We have different shapes and they allow us to process food much more efficiently than something like a shark. If you’ve watched a shark eat, they just chomp chomp, swallow and then they have to digest very slowly this big piece of flesh. Mammals have the ability to do a lot of that processing in their mouths.

12:00

So by the time the food gets into their bellies, they can digest it much more quickly. So it’s a more efficient to have all these different shaped teeth that fit together specially. And so that made mammals very successful in an evolutionary set. I’ve been wondering about this. What the hell is the wisdom tooth for? The wisdom tooth is the last tooth to erupt in our mouth. So on average, we get that third molar about 18 to 20 years of age, if it ever comes. And so that’s a marker of wisdom, because everybody knows that 18 to 20 year olds are the smartest people on the planet.

12:30

And is that the correct term for when a tooth arrives in your face, it erupts? That’s correct. It’s not arriving in your face, it’s actually just coming through your gum line. It’s been there for a long time. I mean, look, potato, potato. If you look at an x-ray, in fact, you’d be shocked that a 10-year-old has all its teeth ready to go. They just may not have all come out yet into the jawbone. I actually freaked out my wife today in showing her a photo of a baby’s skull with all the adult teeth up in its face. Honestly, very disturbing.

12:58

It is fascinating. Small children are just walking teeth everywhere inside their skulls. Honestly, this is becoming way weirder than I thought. Our cavemen are the same as us. And what did they eat? What did cavemen eat? They ate probably everything they could find that moved. They weren’t very picky, particularly in those difficult periods in the ice ages when food was pretty hard to come by.

13:22

We have a lot of evidence from everything from the chemistry of teeth to the stuff that sticks to your teeth called calculus. We can find evidence of ancient diets even just trapped on fossil teeth. You can scrape that off and put it under a microscope and see things like starch and pollens can be extracted from just the goo on your teeth. How can you tell what someone’s eaten from a hundred thousand years ago? Well teeth have a chemical signature in them that reflects what an individual was eating when it was growing their teeth. So if you had a

13:51

particularly high in a certain type of plant, you’ll have a slightly different chemistry than Tom would if he was eating a different type of plant that has a different chemical signature. So we can take teeth, analyze their chemistry, and actually say something about these broad dietary groupings even inside them. Now, also, as I said, the stuff on the outsides traps that information too. So you put all that together. You look at the chemistry of the hard tissues. You look at the stuff left on the outsides.

14:17

And sometimes you even look at the scratches to infer what people are eating. So we use all that evidence to come up with dietary change through time. With all this teeth, what does that tell you about humanity now? When I say teeth are time machines, I mean, not only are they a great record to our past because they stick around, they’re almost like fossils in our mouths. So we find many of them in the fossil record. They’re also time machines because they have tiny timelines inside them. So when you’re growing your teeth, you actually record every single day of your childhood. Like the lines of a tree or something like that.

14:46

Even better, daily ones. Daily. Trees have annual rhythms, right, that you can see on the tree trunk. Yeah. But teeth have daily rhythms. Wow, they must be really, really tiny. They are very, very tiny. We need microscopes to peer inside them, in fact, because they are so hard you can’t see them with your eyes. Once we get past our late adolescence, we don’t add any more time to our teeth. So that’s really when the record ends from my perspective. OK, so you basically dead rocks in your face.

15:14

We prefer to call them fossils in our mouth. Mouth fossils. One of my big projects was looking at Neanderthal children, some as young as three years of age. And I was able to count all these tiny timelines to figure out how fast it took them to grow all their teeth and show that actually they grew up faster than human children do today. If you have something that lives shorter, they generally have a lot more energy, like little dogs or even insects. You’re talking in part about what we call metabolic rate, like how fast our body burns fuel.

#### 15:41

We tend to be slow burning relative to things like mice and other small-bodied organisms that need to eat constantly because their metabolism is so high. We’re a little bit on the slower lane, but Neanderthals, you know, they were very active. You know, we can tell from their bones they have big muscle attachments and so having big muscles means you need to have a high energy diet. So we think they had probably a need for more calories on a daily basis than people living today. Wow, that’s incredible. So they were really just running around just hitting dinosaurs on the head with the stick to get food into.

16:11

You had to slip in the dinosaur. I knew it. I knew it was coming. No dinosaurs, everybody. Just to be clear, they did not overlap in time. When you hear that, does that set your teeth on itch? I’m grinding them right now. Whenever you go to parties, dude, people cover their mouths with their hands and just go, yeah, nice to meet you. Because you could tell what people have been doing all their life from their teeth. Yeah, you look at their mouth and you’re like, you stole a car when you were 19. Well, I usually study teeth from people

16:41

that it’s not really too threatening to most people I meet on the street. And what I do when I study them is I actually have to cut them up. So most people don’t really want to hand over a tooth. I heard there used to be human hobbits. Is that true? There certainly were ancient hominins that were smaller than we are today. For example, in Indonesia on the island of Flores, there were hobbits. How big were they?

17:05

meter tall. A meter? Yeah, they were fairly small. And that’s fully grown adult and like the children would be like half a meter. They would be pretty darn small. They made tools, they hunted animals, but they didn’t look like we do today. Absolutely not. Do you have any fossils of them riding cats or anything like that? No, but there’s giant rats that they apparently hunted that the artistic depictions of them holding the tails with these big rats flapped over their backs. It’s just amazing to imagine these little meter high guys hunting these giant rats. Tiny people and giant rats. Exactly.

17:34

not a great combination. That’ll sound like a pretty out there world. It sounds cool. Yeah. I want a time machine. You have 32 time machines in your FaceTime. Oh, indeed. You’ve read my book. Bum, bum, bum, bum. You can find out the whole tooth about teeth in this book. And the book is called what, Phil? The Tales Teeth Tell. One of my favorite chapters to write was about tooth modification. Turns out that people just a few thousand years ago like to adorn themselves by modifying their teeth. What? Like put bling in their teeth. Exactly.

18:04

They embedded precious gems in their teeth. They sometimes filed and notched their teeth. Did they ever sharpen their teeth into points? They sometimes did. They would make little designs on the edges of teeth. Wow. And they did that all before any kind of novocaine or? Anesthesia, that’s right. You’d have to go like for five minutes to get your teeth slightly drilled and then pass out from pain and then come back the next day.

18:26

Yeah, I mean, you just wonder what people tolerated. Even some societies, they’d knock out teeth as a way of showing cultural affiliation. So imagine just sitting there and having somebody take a rock and a stick and knock out one of your front teeth, because that showed that you belong to them. Someone came up and said, hey, you can join my club, but we need to take one of your front teeth. I’d be like, it’s okay. I’m not that keen. Right. It must have been really important to people to be able to show I’m part of this group because I don’t have front teeth on the top of my tooth, bro.

18:55

So what about tooth operations? Would they perform that kind of thing back then? We have evidence and fact of the first drilling of a cavity about 14,000 years ago. Wow! What do they use? We think they use something called a bow drill. So by using a bow drill, you basically just swirl a stick back and forth between your hands as fast as possible that creates friction. The stick will actually drill into something. So someone’s just holding a stick into your mouth and rotating it. I feel like a bad day at the dentist. Yeah, you hope they’ve got a steady hand.

19:49

I hope they don’t show up. What’s the book called, Will? The Tales Teeth Tale. That is fantastic. It’s really accessible. I’ve actually read most of it, but my kids also have read some of it and they love it as well. And in fact, I got some of these questions from my kids. Well, thank you. One of the things I wanted to do was put as many images as I could in the book and animations and illustrations that people could use to better understand some of the science. Check it out, people. Thank you so much.

19:49

Thank you so much, Tanya, for coming into this show. We really appreciate everything you said has been extremely interesting. I feel like we’ve gone over it with a fine tooth comb. Fine. Well, you guys are a riot. I’ve enjoyed spending this time with you and I hope I’ve given you more to chew over than you possibly could use. And a big thanks to all the kids who submitted their questions. Links to everything we talked about today can be found at smallminds.au. I like the Tanya’s book called The Tales Teeth Tell. We’ll be there as well.

20:16

Keep curious people and keep asking the big questions. Big questions from small minds.